In North America, we commonly buy gifts for our close friends and associates at Christmas and on birthdays, and anticipate in return that a similar group will send gifts our way at the appropriate times. We can feel it, probably as a slight, when we do not receive a gift from a close friend, and we anticipate a bit of shame if we fail to give a gift to an appropriate other.

In North America, we commonly buy gifts for our close friends and associates at Christmas and on birthdays, and anticipate in return that a similar group will send gifts our way at the appropriate times. We can feel it, probably as a slight, when we do not receive a gift from a close friend, and we anticipate a bit of shame if we fail to give a gift to an appropriate other.

What is striking about this situation is that our behaviour is scripted in advance. On a date specified independently of any of us individually, a game of reciprocal exchange is enacted. The rules are fairly clear, and successful (or unsuccessful) playing of the game determines in a significant way how we are understood by others.

This structure, though, sits uncomfortably with the very notion of what a gift is.

Normally, we would think that a gift should be given because of the other person and the unique response that other calls up in oneself. When we give because of the rule, though, our motivation is to play the game right: it is the game that has captured our enthusiasm and commitment, not the person.

Again, we would normally expect of a gift that it be spontaneous: the gift should, effectively, be pulled out of me by your impact upon me. Instead, Christmas shopping is a kind of machine, a premeditated calculation in response to social pressure. For this reason, too, the structure of a rule fits oddly with the notion of a gift.

Finally, giving gifts according to the rule is doing “what one does.” “One” gives a gift, and, similarly, “one” receives a gift—for rules always make a generic address to “one”—and inasmuch as this standard gift-giving is a matter of “one” giving to “one,” the gift does not mark a reality uniquely constituted by our specificities. But, again, the notion of a gift is precisely the notion of something that I specifically want for you specifically.

For these three reasons, then—institutionality, calculation and impersonality—the regularized practices of gift-giving that we typically rely upon run afoul in principle of the very nature and meaning of a gift.

There are at least two important things to learn here.

The first lesson is a simple, personal one: we should note how much we rely upon the rule of gift-giving, (which, as we’ve seen, paradoxically means precisely the rule not truly to give a gift), and in fact do very little in our lives to carry out a more authentic attitude of giving—“generosity”—with our friends. We should be more generous.

The first lesson is a simple, personal one: we should note how much we rely upon the rule of gift-giving, (which, as we’ve seen, paradoxically means precisely the rule not truly to give a gift), and in fact do very little in our lives to carry out a more authentic attitude of giving—“generosity”—with our friends. We should be more generous.

The second lesson is more complicated. To understand it, we must ask, “And what will a gift be, then, if I give for real, rather than relying upon the standard rules?”

Whereas the “gift” in the Christmas-game is a playing piece in a system of reciprocal exchange according to which what one gives to another is supposed to be met with an equivalent return “gift,” the gift that is the spontaneous offer of oneself or one’s own to another expends itself entirely in the giving and seeks no return. And, indeed, no reciprocal gift would be possible, for the uniqueness of the giving—its unique responsiveness to the specificities of the situation—make it incomparable to any other. A different gift could be given, but that would simply be another unique event of generosity uniquely defined by its situation and in no way “compensating” for the original gift.

The generosity of the true gift does not seek to be “paid back”—indeed, to give is precisely to renounce relating to the other according to the rules of reciprocal exchange—but in a sense very different from that operative in the gift-game, to receive the gift is to take on an awesome “debt.” The gift does not require to be paid back, but what it does is call one to embrace the relationship authentically. This is the second, more challenging lesson.

A true gift is a great challenge, for, at the same time as it is a gesture that breaks out of the rule of reciprocal exchange, it is a call to the other not to live according to those rules. The gift expresses that persons should spontaneously give themselves to each other in response to their unique specificities, and thus the gift is in fact a form of critique—it effectively accuses one of behaving badly if one does relate to others according to the rules of institutional, calculative impersonality.

True generosity is an insistence on authenticity and thus, though it asks for no “payback,” it imparts an imperative to the other to rise to the demands of relating to others authentically. To participate truly in gift-giving is to hear the call to give up treating the other as something that fits into well-defined, pre-scripted roles; it is the call to be open to having to define unique ways of relating to unique others rather than relying upon the comfortable terms of our established social expectations.

So the gift that is really without price is the one that has the highest price-tag of all, for to receive it is to receive the call to hold oneself responsible for caring for the unique worth of the other, a worth that is infinite in that no limit set from without can do justice to it.

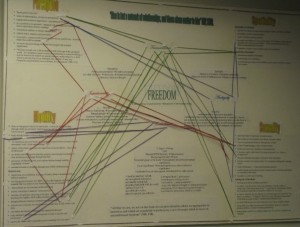

Participants in these

seminars consistently have the experience of growth in their conversation and

conceptual abilities, and typically leave with a transformed sense of the nature

and possibilities of philosophy.

Participants in these

seminars consistently have the experience of growth in their conversation and

conceptual abilities, and typically leave with a transformed sense of the nature

and possibilities of philosophy.