Our everyday perceptual life is a back and forth exchange with the environment that is characterized by, among other things, a constant novelty in our awareness—I find out, through perception, that a man is arguing with his daughter in that house, but I didn’t know that until I came upon the scene and heard them quarrelling. Though by and large our core sense of our environment remains constant throughout the day, we nonetheless are constantly making discoveries about what is going on in this world as we carry out our day’s activities.

This experience of discovery is magnified further by our practices of conversation. Throughout the day, we meet with others—friends and strangers—and with them we respond to the impulse to put our experience of our situations into words. Even more than in our silent interaction with the world, our linguistic interaction with other people allows us to discover aspects of the world otherwise unknown to us—through language, we are enabled, effectively, to “see through the other’s eyes,” and reshape our own perspective through the discovery of how another perceives.

It is this basic sense of perceptual discovery that we underscore and emphasize when we self-consciously engage in the practice of learning. (And turning to books and to lecturers is, of course, a self-conscious deployment of the everyday power of language to allow us to partake in the perspectives of others.) In our self-conscious projects of learning, we take the everyday experience of discovery and pursue it as such. Instead of simply responding to what shows itself spontaneously, we actively ask, “What can be found here?” “How can I see into my situation—my world—more deeply?”

It is this basic sense of perceptual discovery that we underscore and emphasize when we self-consciously engage in the practice of learning. (And turning to books and to lecturers is, of course, a self-conscious deployment of the everyday power of language to allow us to partake in the perspectives of others.) In our self-conscious projects of learning, we take the everyday experience of discovery and pursue it as such. Instead of simply responding to what shows itself spontaneously, we actively ask, “What can be found here?” “How can I see into my situation—my world—more deeply?”

When we take up this project, we discover that there is a lot to learn.

On the one hand, the world offers us an inexhaustible domain of fact. Just within one’s immediate perspective, the list is endless: the store is open; there are two women sitting at the table; the coffee is cold; and the list could just go on and on.  In the larger word, a similarly infinite list: it is noon in Damascus; there is heavy rain in Chennai; the President of the United States is delivering a speech; the students in Montréal are gathering on rue Ste.-Catherine. And when we step beyond the immediate present to what has been, a veritable abyss opens: Mohammad died in 632 A.D.; the caves at Chauvet were painted 35,000 years ago; Socrates was executed in 399 B.C.; the Bretton-Woods Agreement was signed in July 1944; etc., etc.

In the larger word, a similarly infinite list: it is noon in Damascus; there is heavy rain in Chennai; the President of the United States is delivering a speech; the students in Montréal are gathering on rue Ste.-Catherine. And when we step beyond the immediate present to what has been, a veritable abyss opens: Mohammad died in 632 A.D.; the caves at Chauvet were painted 35,000 years ago; Socrates was executed in 399 B.C.; the Bretton-Woods Agreement was signed in July 1944; etc., etc.

It is a very limited conception of learning, however, (and one often implicitly or explicitly endorsed, unfortunately for us all, by novice students, by parents, and by educational theorists or policy-makers), to imagine the acquisition of fact to be the primary or even the exclusive phenomenon of learning. Facts are important, but that very notion—importance—is not itself a matter of fact.

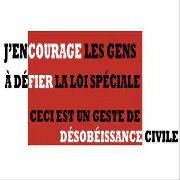

More so that apprehending fact, learning is importantly a matter of developing insight. Learning is most basically a matter of improving our understanding of the facts that confront us. Understanding is not itself an apprehension of fact, but is a grasp of the intelligible principle that allows us to interpret the significance of what we encounter. It is one thing to know that students are gathering on Ste.-Catherine; it is something else to recognize that one is witnessing a public outcry against unjust or even illegal practices of the Quebec government.

And once one recognizes this priority of insight, the easy association of education with the acquisition of fact—“information”—faces a further challenge. The essential role of interpretation in recognizing the significance in our situations in fact compromises the putative simplicity of recognizing “facts.”  Is it a fact that George W. Bush was the 43rd President of the United States? One might have thought the answer was obviously “yes,” but in fact the answer to this depends upon what “President of the United States” means. Is the President the one generally recognized by the population? The one recognized by the courts? The one who legitimately won the position according to the rules and laws surrounding elections? The one who enacts policy in the interest of the nation? These are all plausible criteria for justifying the use of that name, but they do not necessarily point in the same direction. It has been alleged, for example, that the election in this case was compromised, and did not in fact follow election laws. If this is true, then it is not the case that this is the individual who was elected, properly speaking. It has also been alleged, for example, that this individual did not pursue policy in the public interest. Again, if this is true, then, though this individual was recognized by many as “President,” properly speaking he may not, according to the fourth criterion, have held that title. Indeed, in that case, there may be no “fact of the matter” regarding “who was the 43rd President of the United States?”

Is it a fact that George W. Bush was the 43rd President of the United States? One might have thought the answer was obviously “yes,” but in fact the answer to this depends upon what “President of the United States” means. Is the President the one generally recognized by the population? The one recognized by the courts? The one who legitimately won the position according to the rules and laws surrounding elections? The one who enacts policy in the interest of the nation? These are all plausible criteria for justifying the use of that name, but they do not necessarily point in the same direction. It has been alleged, for example, that the election in this case was compromised, and did not in fact follow election laws. If this is true, then it is not the case that this is the individual who was elected, properly speaking. It has also been alleged, for example, that this individual did not pursue policy in the public interest. Again, if this is true, then, though this individual was recognized by many as “President,” properly speaking he may not, according to the fourth criterion, have held that title. Indeed, in that case, there may be no “fact of the matter” regarding “who was the 43rd President of the United States?”

Similar complexities attach to other notions that we often treat simply as matters of fact. Is it true that Jean Valjean stole bread (in Vico Hugo’s Les Miserables)? No doubt he seized the loaf with his hand and took it for his family’s use. Is this theft, though? That depends on how we determine ownership. Though the police and the courts recognize the shopkeeper as the owner, we might well disagree that these are the relevant agents, and argue instead that that shopkeeper possessed the bread only because of the operations of a larger economic system that unjustly exploits the working population, that is, it is a system that steals from the poor. In that case, Valjean’s actions would simply be a retrieval of wealth that was unjustly stolen from him. In the case of “theft,” in other words, we cannot establish the fact without insight into the nature of the economic situation. In short, what we take to be immediate fact depends in many cases on what we already presume to be the essential “logic” or “mediation” in the situation, and developing a true insight into the situation may result in our having to criticize our own presumptions and, with them, our own beliefs about what are “the facts.”

Insight, then, “trumps” fact in matters of learning; and yet, even insight is not the highest matter here. We typically think of learning as knowing the truth about the world—a matter, that is, of objectivity. In its most important forms, though, true learning does not leave us untouched, but is a matter of existential change—a matter, as Kierkegaard wrote, of subjectivity.  Should we learn the truth that Jean Valjean is (or student protesters in Montréal are) unjustly being seized by the police and then do nothing about it, we are not “neutrally objective”; on the contrary, we are now complicit in the unjust action, and our behaviour is an expression of cowardice or immorality in the face of what we recognize to be a situation of injustice, not an expression of epistemic neutrality. The developing of the insight that challenges our presumptions precisely requires us to change and to act—it precisely requires us to recognize that our situation cannot be divorced from ourselves, objectivity cannot be divorced from subjectivity.

Should we learn the truth that Jean Valjean is (or student protesters in Montréal are) unjustly being seized by the police and then do nothing about it, we are not “neutrally objective”; on the contrary, we are now complicit in the unjust action, and our behaviour is an expression of cowardice or immorality in the face of what we recognize to be a situation of injustice, not an expression of epistemic neutrality. The developing of the insight that challenges our presumptions precisely requires us to change and to act—it precisely requires us to recognize that our situation cannot be divorced from ourselves, objectivity cannot be divorced from subjectivity.

This, it seems to me, is the ultimate goal of education: to find in our situations the compelling imperative to render justice to those situations. Education, though it begins with the recognition of fact, must be oriented towards the cultivation of insight into the deeper mediation in our situations for the sake, ultimately, of precipitating in us a turn to our subjectivity that is simultaneously a criticism of our prejudices and a change in our behaviour. Education, in short, is ultimately about becoming better persons. Education is not living up to its intrinsic mandate if it is not ultimately serving to cultivate our characters such that we become courageous in responsibly answering to the demands of our situations.

Participants in these

seminars consistently have the experience of growth in their conversation and

conceptual abilities, and typically leave with a transformed sense of the nature

and possibilities of philosophy.

Participants in these

seminars consistently have the experience of growth in their conversation and

conceptual abilities, and typically leave with a transformed sense of the nature

and possibilities of philosophy.

One Comment

Wow! This is an excellent post to use for the first day of class. For that matter, I think it could be excellent for an editorial column in a newspaper. But I usually think these things about your writing.